No-one would want to work without getting a salary, or even worse – having to pay to be there.

Yet paying companies so you can pretend to work for them has become popular among young, unemployed adults in China. It has led to a growing number of such providers.

The development comes amid China’s sluggish economy and jobs market. Chinese youth unemployment remains stubbornly high, at more than 14%.

With real jobs increasingly hard to come by, some young adults would rather pay to go into an office than be just stuck at home.

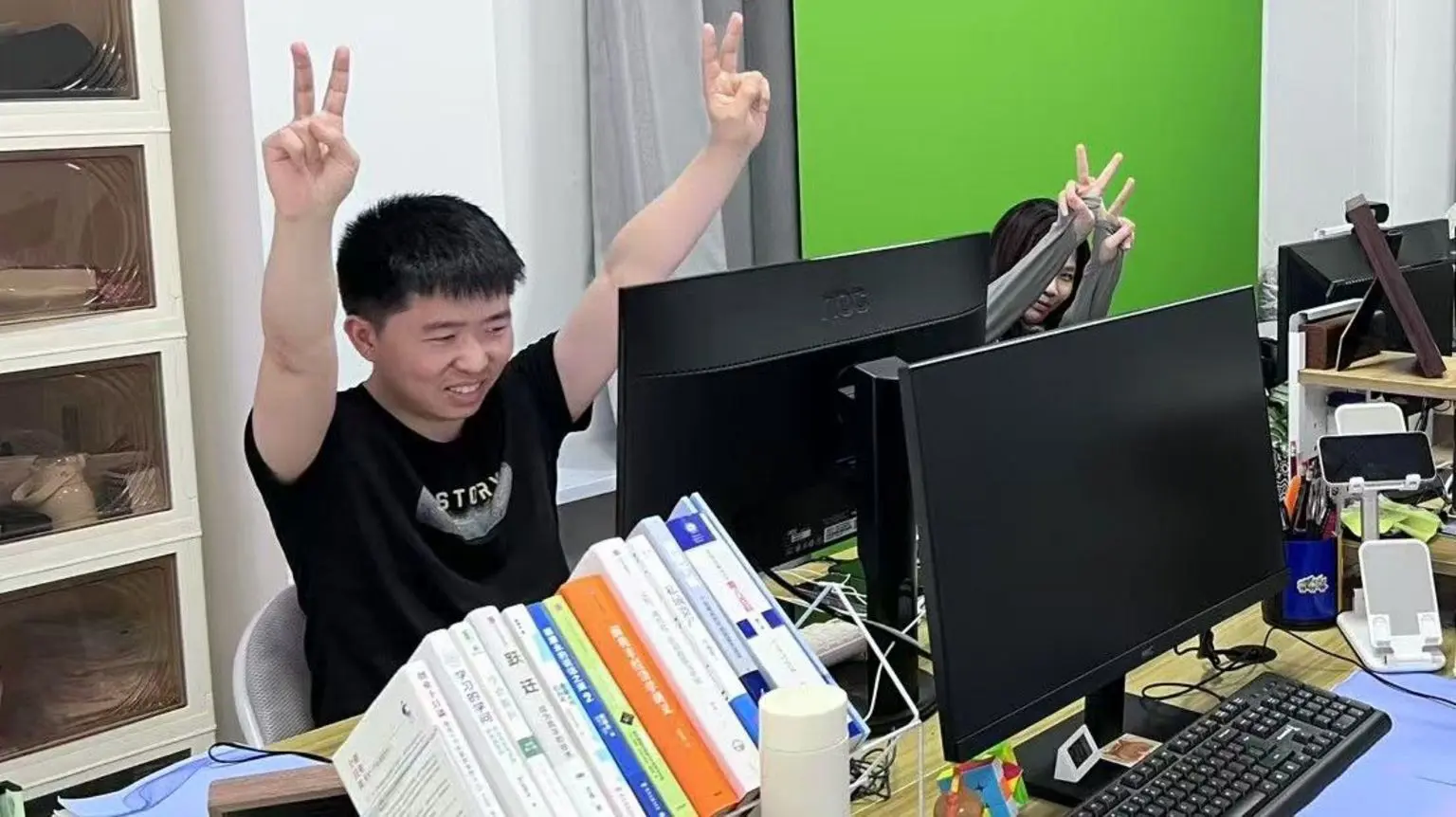

Shui Zhou, 30, had a food business venture that failed in 2024. In April of this year, he started to pay 30 yuan ($4.20; £3.10) per day to go into a mock-up office run by a business called Pretend To Work Company, in the city of Dongguan, 114 km (71 miles) north of Hong Kong.

There he joins five “colleagues” who are doing the same thing.

“I feel very happy,” says Zhou. “It’s like we’re working together as a group.”

Such operations are now appearing in major cities across China, including Shenzhen, Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuhan, Chengdu, and Kunming. More often they look like fully-functional offices, and are equipped with computers, internet access, meeting rooms, and tea rooms.

And rather than attendees just sitting around, they can use the computers to search for jobs, or to try to launch their own start-up businesses. Sometimes the daily fee, usually between 30 and 50 yuan, includes lunch, snacks and drinks.

Dr Christian Yao, a senior lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington’s School of Management in New Zealand, is an expert on the Chinese economy.

“The phenomenon of pretending to work is now very common,” he says. “Due to economic transformation and the mismatch between education and the job market, young people need these places to think about their next steps, or to do odd jobs as a transition.

“Pretend office companies are one of the transitional solutions.”

Zhou came across the Pretend To Work Company while browsing social media site Xiaohongshu. He says he felt that the office environment would improve his self-discipline. He has now been there for more than three months.

Zhou sent photos of the office to his parents, and he says they feel much more at ease about his lack of employment.

While attendees can arrive and leave whenever they want, Zhou usually gets to the office between 8am and 9am. Sometimes he doesn’t leave until 11pm, only departing after the manager of the business has left.

He adds that the other people there are now like friends. He says that when someone is busy, such as job hunting, they work hard, but when they have free time they chat, joke about, and play games. And they often have dinner together after work.

Zhou says that he likes this team building, and that he is much happier than before he joined.

In Shanghai, Xiaowen Tang rented a workstation at a pretend work company in Shanghai for a month earlier this year. The 23-year-old graduated from university last year and hasn’t found a full-time job yet.

Her university has an unwritten rule that students must sign an employment contract or provide proof of internship within one year of graduation; otherwise, they won’t receive a diploma.

She sent the office scene to the school as proof of her internship. In reality, she paid the daily fee, and sat in the office writing online novels to earn some pocket money.

“If you’re going to fake it, just fake it to the end,” says Tang.

Dr Biao Xiang, director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Germany, says that China’s pretending to work trend comes from a “sense of frustration and powerlessness” regarding a lack of job opportunities.

“Pretending to work is a shell that young people find for themselves, creating a slight distance from mainstream society and giving themselves a little space.”

The owner of the Pretend To Work Company in the city of Dongguan is 30-year-old Feiyu (a pseudonym). “What I’m selling isn’t a workstation, but the dignity of not being a useless person,” he says.

He himself has been unemployed in the past, after a previous retail business that he owned had to close during the Covid pandemic. “I was very depressed and a bit self-destructive,” he recalls. “You wanted to turn the tide, but you were powerless.”

In April of this year he started to advertise Pretend To Work, and within a month all the workstations were full. Would-be new joiners have to apply.

Feiyu say that 40% of customers are recent university graduates who come to take photos to prove their internship experience to their former tutors. While a small number of them come to help deal with pressure from their parents.

Інші 60% — фрілансери, багато з яких — цифрові кочівники, зокрема ті, хто працює у великих компаніях електронної комерції, і автори кіберпростору. Середній вік – близько 30 років, наймолодшому – 25.

Офіційно цих працівників називають «професіоналами з гнучким працевлаштуванням» — групою, яка також включає водіїв вантажівок і водіїв вантажівок.

У довгостроковій перспективі Фейю каже, що сумнівно, чи залишиться бізнес прибутковим. Натомість він більше любить розглядати це як соціальний експеримент.

«Він використовує брехню, щоб зберегти респектабельність, але це дозволяє деяким людям знайти правду», — каже він. «Якщо ми лише допомагаємо користувачам продовжити їхні акторські навички, ми беремо участь у обережному обмані.

«Цей соціальний експеримент зможе справді виправдати свої обіцянки, лише якщо допомогти їм перетворити їхнє фальшиве робоче місце на справжню відправну точку».

Зараз Чжоу витрачає більшу частину свого часу на вдосконалення своїх навичок ШІ. Він каже, що помітив, що деякі компанії вказують на знання інструментів штучного інтелекту під час найму. Тому він вважає, що отримання таких навичок штучного інтелекту «полегшить» йому пошук повної роботи.

Залишити відповідь